By Brian Boone

The Brooklyn Bridge is a landmark and a wonder of 19th century engineering. Due to multiple tragedies, it almost didn’t get built—until a self-taught math and science genius took the reins of the project, despite women working in that field was unheard of at the time. Here’s the amazing story of Emily Warren Roebling, the woman who made the Brooklyn Bridge happen.

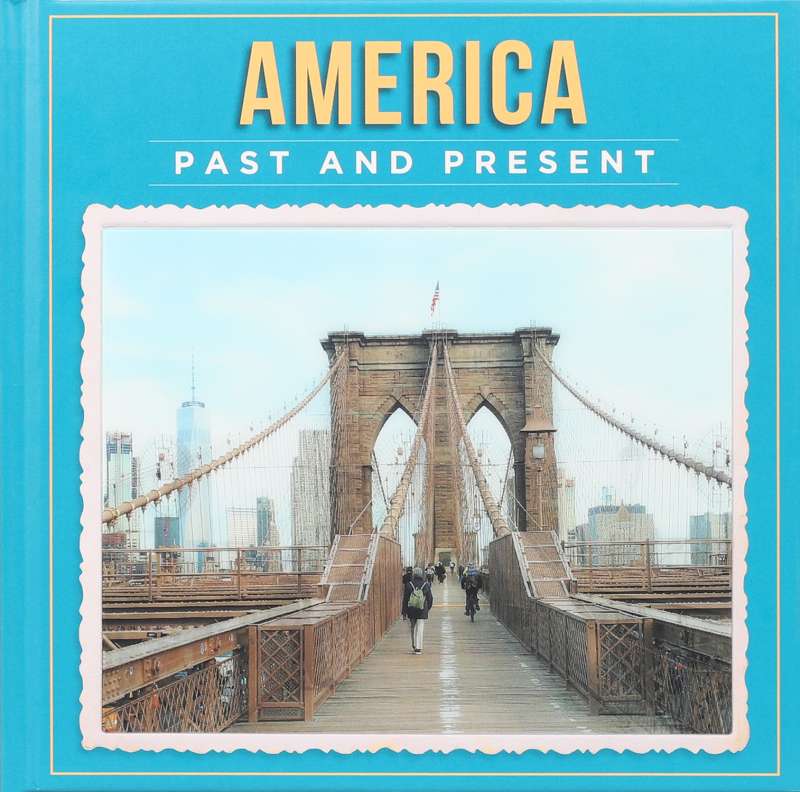

Experience America's ever-changing landscape in this fascinating visual guide.

Roebling No. 1

In 1867, the New York State Senate-funded New York and Brooklyn Bridge Company hired German-American engineer John A. Roebling to design and oversee construction on an ambitious project. First proposed in the early 1800s, New York City needed a bridge over the East River to connect the booming boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Roebling, who’d built suspension aqueducts and several bridges and ran his own cable and wire company, took the job, which would be the longest suspension bridge in the world, and the first ever to employ the use of steel cables.

Roebling No. 2

After designing the blueprint for the massive Brooklyn Bridge—set to be nearly 1,600 feet long with a deck more than 100 feet above the water, supported by caissons sealed, pressurized, and placed underwater—Roebling suffered an accident while surveying the construction site. He contracted tetanus and died. Control of the project ceded to his son, Washington Roebling, also a talented and trained engineer who’d been instrumental in planning the Brooklyn Bridge. He’d accompanied his father on a two-year trip in Europe researching suspension and caisson technology. And inside of those is where he chose to work, until 1870, when prolonged exposure to compressed air and survival of a fire left Roebling with a debilitating case of decompression sickness, also known as “the bends.” Roebling would spend the rest of his life in bed coping with physical and mental illness.

Roebling No. 3

Washington Roebling’s wife, Emily Warren Roebling, grew up as a socialite in a prominent East Coast family. Discouraged from seeking out higher education, as it wasn’t proper for a lady of the era to do so, Warren Roebling went anyway, and studied advanced mathematics and science. She also went with her husband and father-in-law to Europe in the 1860s, absorbing the principles of bridge construction and engineering before further teaching herself the rest of what she wanted to know. It came in hand, because after her husband’s accident in 1870, Emily Warren Roebling became the de facto head of the Brooklyn Bridge construction project.

Knowledge Bridge

During periods of lucidity, Washington dictated extremely detailed instructions to Emily on everything yet to be done on the Bridge. She copied down what he said, then added her own expertise and analysis, and delivered it to her crews back at the construction site (and communicated questions and issues back to Washington). To supplement all that, Emily Warren Roebling studied relative material strength, conducted stress analysis studies, researched cable construction, and visited other, similar construction projects for research. In the evenings, Emily attended society events as a representative of the highly anticipated Brooklyn Bridge project and reportedly spoke so voluminously and expertly about the design and construction that rumors persisted that she had actually designed the bridge from day one, and her husband and father-in-law had just been fronts.

A Bridge Too Far?

The Brooklyn Bridge officially opened for traffic with a big public ceremony on May 24, 1883. The first people to cross it, in a carriage: President Chester Alan Arthur, and the project’s leader and public face, Emily Warren Roebling. She brought along a third commuter in the carriage: a rooster. She said it was to represent victory, and also served as a good-luck charm.

The public remained unconvinced that this new bridge—so large and based on such relatively new technology—could be trusted. Rumors spread through Brooklyn and Manhattan that a full-on collapse was both inevitable and imminent. Six days after it opened, a woman fell down the stairs on the bridge’s Manhattan side. With tensions high, another woman screamed at the sight, leading to a riot of panic. The resultant stampede of upset pedestrians on the stairwell led to a crush of bodies and tragedy—12 people died that day.

It would take circus impresario and publicity master P.T. Barnum to assuage fears about the Brooklyn Bridge. In May 1884, he marched 12 circus elephants across the bridge. That’s a heavy load, and the bridge sustained it.

Emily Warren Roebling’s reputation was saved.

The Brooklyn Bridge is just one of the United States’ many architectural marvels. Get fascinated by ingenuity and the can-do spirit with Robin Pridy’s America Past and Present. Look for this remarkable photography collection with the Brooklyn Bridge on the cover—it’s available now wherever books are sold.